T&T’s External Buffers

Commentary

The Trinidad and Tobago (T&T) economy is synonymous with oil and gas. The sector contributes considerably to the government’s coffers and is a key earner of foreign exchange. Over the past few decades, energy windfalls have been the catalyst for further expansion of and reinvestment into the energy sector and have facilitated significant economic linkages, resulting in notable economic development. While the dynamics of the industry have evolved over the past few years, its importance remains paramount to T&T’s overall performance to date. The economic cycle of T&T closely mirrors the movement of energy prices, specifically oil prices. Accordingly, the fact that T&T is a price taker on the international energy market renders the economy highly susceptible to energy price swings. Though the domestic energy sector has been undergoing a protracted period of weakness due to production constraints, the strength of the sector, especially in the boom years allowed for the accumulation of foreign exchange buffers with strong foreign exchange reserves as well as the sizeable sovereign wealth fund, the Heritage and Stabilization fund (HSF). These external buffers have augured well for the T&T economy, helping to stabilize the external and fiscal positions particularly during downturns and have been a key credit strength for the sovereign from a credit rating perspective.

T&T’s Energy Sector Contribution

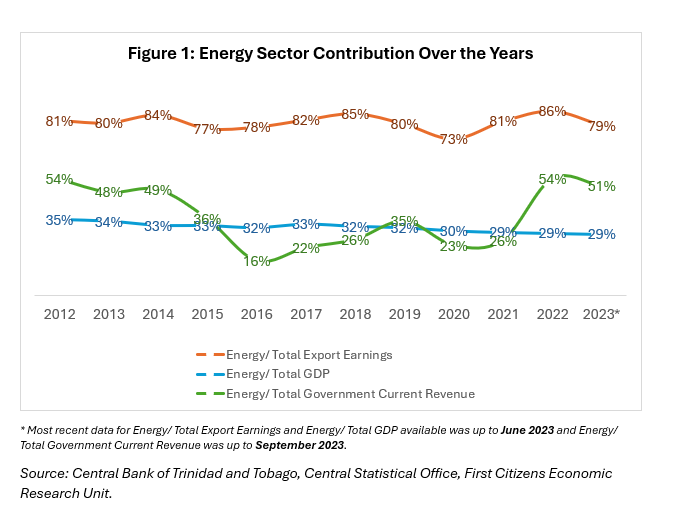

The energy sector is a significant economic contributor for T&T. According to data from the Central Statistical Office (CSO), at the end of the second quarter of 2023, the energy sector accounted for approximately 28.6% of total GDP in constant prices. While its share has fallen over the years from around 35% in 2012, it remains systematically important. The sector is by far the largest export earner in the country, accounting for upward of 75% of total export earnings. Government revenue from the energy sector has been volatile over the years, and reflects the performance of global energy prices, notwithstanding, it has averaged 40% of government’s current revenue since 2000, peaking at 58% in 2011 and dropping to a low of 16% in 2016. At the end of the fiscal year ended September 2023, energy sector revenue accounted for 51% of current revenue, falling slightly from its 54% share in FY 2022.

Foreign exchange reserves trends

Historical Context

According to the Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago (CBTT), “International reserves are defined as external assets that are readily available to and controlled by monetary authorities for direct financing of payments imbalances, for indirectly regulating the magnitudes of such imbalances through intervention in exchange markets and for other purposes. Typically, they include a country’s holding of foreign currency and deposits, securities, gold, IMF special drawing rights (SDRs), reserve position in the IMF, and other claims.”

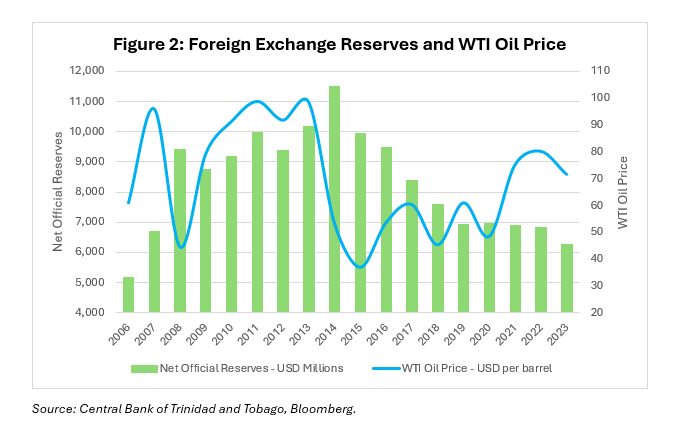

As a key earner of foreign exchange, the energy sector has contributed significantly to the healthy accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, especially during the oil price boom years. FX reserves peaked at around USD11.5 billion at the end of 2014, driven largely by the record high WTI oil price in the preceding period 2011-2013, when it averaged around USD97 per barrel. Prices continued to soar and averaged USD102 per barrel for the first half of 2014. However, it subsequently sank to an average of USD81 per barrel in the second half, consistently fell to end 2014 at a price of USD53.27.

Prices continued their precipitous decline, ending 2015 at a low of USD37.04. The 60% price plunge between 2013 and 2015 was one of the three biggest declines since World War II and the longest lasting since the 1986 oil price collapse, according to the World Bank. The dynamics of the energy markets had changed due to the emergence of US shale oil production, which resulted in a significant supply glut, causing prices to plummet. These wild swings in global oil prices had significant implications for T&T.

Around the same time, T&T’s domestic energy production levels were on the decline. During the period 2013-2015, crude oil production had fallen by 3%, natural gas production by 8% and LNG production declined by a sharper 12%. The falloff in output resulted in weaker performances throughout the rest of the energy sector.

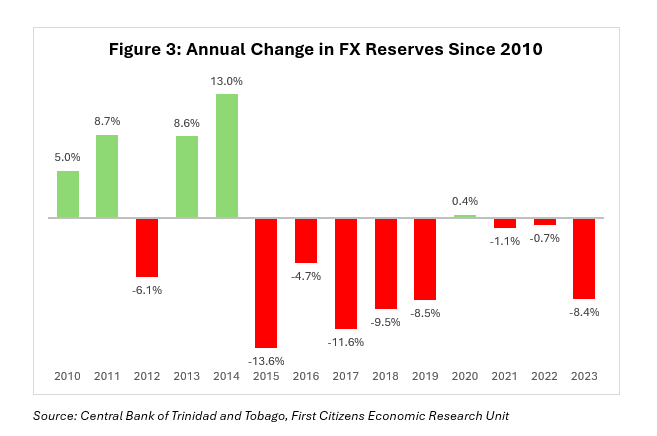

Accordingly, the combination of significantly lower prices and falling production resulted in a sharp and steady decline in the country’s FX reserves post-2014. Between 2014 and 2015 alone, FX reserves dropped by USD1.6 billion, or by 14%, and the decline has persisted up to 2023, except for a small uptick of 0.4% in 2020. (See figure 3). Between 2014 and 2023, the country’s FX reserves were down by around 45%, while at the same time, WTI oil prices were around 2% up, on average during those years (notwithstanding the notable annual volatility during the period).

Recent Developments

Following the 55% increase in WTI oil price in 2021 due to post-pandemic demand as well as heightened geopolitical risks in Europe, prices continued to rally, advancing a further 7% in 2022. This led to a smaller decline in FX reserves, even as imports rose sharply in both years. Further, in August 2021, T&T benefitted from around USD644 million in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the IMF, providing a much-needed bump, resulting in a USD477 million increase in reserves during July and August 2021. This helped to stem the erosion and helped to push it back above the USD7 billion mark for the first time since November 2020. Since then, the downward trend has resumed, with 2023 alone recording a relatively steep drop of 8.4%, ending the year at USD6.3 billion. Year to date up to March 2024, FX reserves are down 12% and have been under the USD6 billion threshold – the first time since early 2007. Despite the decline, the country’s import cover remains well above international benchmark requirements. According to the CBTT, is ‘used to measure the adequacy of a country’s international reserves. It essentially computes the number of months the country’s reserves would last if used to fund future (prospective) imports.’ The import cover stood at 6.8 months at the end of April 2024, compared to 7.8 months in December 2023, above the benchmark of at least three months and six months for oil-exporting countries.

Government debt service obligations have been one of the drivers of the decline in reserves. Over the past ten years, the central government external debt increased from 7.9% of GDP to 17.1% of GDP and has significantly increased as a share of total debt, moving from around 18% to currently around 30%. The central government’s external debt service has also increased over the past decade, from USD156.2 million in 2014 to USD655.6 million at the end of 2023. In January 2024, the Government of Trinidad and Tobago (GOTT) 4.375%, USD500 million 2024 Eurobond matured, partially accounting for the fall in FX reserves.

Demand for FX continues to significantly outpace supply, creating severe imbalances in the market, putting pressure on the managed exchange rate. As total system FX sales far outstrips total purchases over the past years, the deficit (difference between supply and demand of FX) has averaged around USD1.5 billion since 2014. In the first four months of 2024, the CBTT has intervened to the tune of USD400 million. While the CBTT support via intervention is necessary for the banking FX system, it contributes to the erosion of FX reserves.

Sovereign Wealth Fund

Another critical external cushion is the country’s sovereign wealth fund – the HSF, which was established in 2007. According to the HSF Act, the purpose of the Fund is ‘to save and invest surplus petroleum revenue derived from production business in order to:

- Cushion the impact on or sustain public expenditure capacity during periods of revenue downturn, whether caused by A fall in prices of crude oil or natural gas.

- Generate an alternate stream of income to support public expenditure capacity as A result of revenue downturn caused by the depletion of non-renewable petroleum resources.

- Provide a heritage for future generations of citizens of T&T from savings and investment income derived from the excess petroleum revenues.’

The HSF Act outlines both deposit as well as withdrawal rules, where a minimum of 60% of the total excess (difference between estimated and actual) revenues must be deposited during a financial year. Similarly, withdrawals may be made from the Fund where petroleum revenues collected in any financial year may fall below the budgeted petroleum revenues for that year by at least 10% but is limited to 60% of the amount of the shortfall of petroleum revenue for the relevant year and 25% of the balance of the Fund at the beginning of that year, whichever is the lesser amount. Further, the act states that no withdrawal may be made from the Fund in any financial year where the balance of the Fund will fall below USD1 billion if such withdrawal was to be made. In 2020, the Act was amended to expand the purpose of the Fund to include fiscal support for the following events:

- A disaster area is declared under the Disaster Measures Act

- A dangerous infectious disease is declared under the Public Health Ordinance Act

- There is, or likely to be, a precipitous decline in budgeted revenues which are based on the production or price of crude oil or natural gas.

As at the end of FY2023 (September 2023), the net asset value (NAV) of the HSF stood at USD5.39 billion, up 14% from September 2022. Despite a deposit of USD164 million during FY2022 (a requirement under the Act since energy revenue exceeded budget estimated by approximately TTD3.9 billion for the FY), the Fund lost almost 14% (yoy), due largely to the underperformance of the global financial market. In FY 2023, while there were no deposits into the HSF, the NAV rose due to much improved returns on assets in which the Fund is invested. During the FY, the HSF recorded a total comprehensive income of USD494.6 million, which is the second highest since its inception, driven by a strong uptick in its equity investments, which returned 9.24%.

Importance of managing external buffers

According to Standard and Poor’s, ‘the government’s large liquid financial assets mitigate the effect of economic cycles on the country’s fiscal performance.’ These liquid assets consist of T&T’s HSF, treasury assets held at the CBTT and liquid assets of the National Insurance Board of Trinidad and Tobago (NIBTT) and based on S&P data, these assets have averaged around 47% of GDP since 2018. S&P also forecasts that HSF liquid assets alone will average more than 14% of GDP during 2023 – 2024.

It is imperative that the country’s external buffers are carefully managed given their importance in mitigating both fiscal and external financing risks, and to ultimately support T&T’s credit rating, which is currently at BBB- (stable outlook) – just one notch above the non-investment grade spectrum. The persistent imbalance in FX supply vs demand and the follow-on impact on the country’s reserves is concerning. The growing external public sector debt is also likely to put pressure on reserves, given that external debt servicing will increase. The main driver of the FX earnings in T&T – the energy sector, remains quite volatile from a price perspective. Added to those uncertainties, is the challenge experienced on the domestic production side. However, the outlook for energy production is more favourable in the medium-term, given the project pipeline and this should help stem the decline in FX reserves in the medium-term. Further, the recent robustness of the non-energy sector can provide some level of support, particularly export-oriented industries, and have the potential to earn foreign exchange.

Structurally shifting the economy of T&T to diversify not just the economy away from energy, but equally as important, diversify the country’s export and government revenue bases in a substantial and sustainable way, is necessary. Only then can we reduce the economy’s vulnerability to external energy price shocks and reduce the volatility that they create in both the fiscal and external accounts. Until such time, the need to prudently manage the country’s external buffers is of paramount importance.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.