Food Security in the Caribbean

Commentary

Food Security in the Caribbean – CARICOM 25 by 2025

Food Security is described by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as “when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” Simply put, it is the ability of individuals to not only have access, but to be able to afford nutritious food. In recent times, events in the global landscape have elevated food security concerns, including the COVID-19 pandemic, cross border conflicts, and trade disruptions. The World Food Programme’s “Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC) 2024” notes that 2023 was the fifth consecutive year that the number of persons facing high levels of acute food insecurity increased to 281.6 million out of a sample set of 1.3 billion persons, or roughly 21.6% of the sample population. The sample population largely consisted of African and Middle Eastern countries, with small representation from Asia, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean.

In a separate report published by the FAO entitled “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World Report 2023”, the Caribbean food security challenges are more prominently highlighted. The Caribbean has one of the highest levels of food insecurity in the world, with the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity as a percentage of the total population estimated at 58.8% (28.6 million individuals) as of 2023, a decline from 60.5% in 2022, but well above the global average of 28.9%. This is comparable to the continent of Africa which had a prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity proportion of 58% in 2023, and different sub-regions of Sub-Saharan Africa which reached as high as 77.7% in 2023.

Understanding the Caribbean Context

The Caribbean region is characterised by low growth and persistently high current account deficits. One of the main reasons for this is the region’s dependence on consumer commodity imports. The imbalance of Caribbean economies is noted by the IMF to have started in the early 1990s due to a loss in preferential trade agreements with European markets. In addition to this, there was also a “deterioration of the terms of trade, reduced fiscal space, and demographic trends, including emigration of skilled labour.”

The dependence on imports brings into question the relationship between food security and structural accounts for the region due to the ever-expanding amount of foreign exchange required for the food import bill. During periods of severe economic downturns, structural imbalances are exacerbated, forcing the region to rely on multilateral borrowing. Despite this borrowing, the resulting impact of the downturn on the balance of payments are steep deficits and an erosion of foreign exchange reserves, further fuelling food insecurity fears. Figure 1 below shows the percentage of staple food imported by Caribbean nations for 2020.

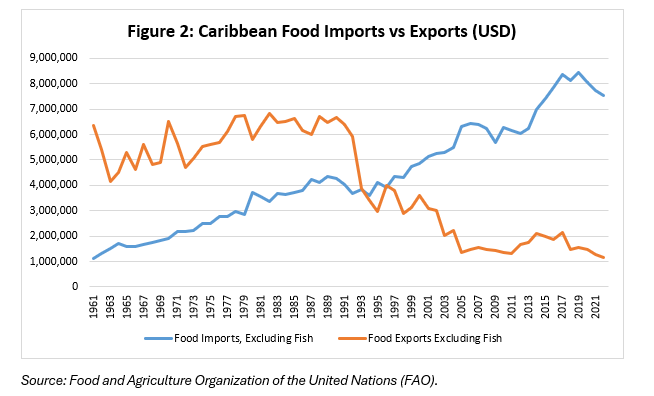

According to the CARICOM Secretariat, between 2000 and 2018 imported food represented approximately 60% of total food consumption in the region, with the figure jumping to as high as 80% in some countries. The latest data from the FAO indicates that the food import bill peaked in 2019 at USD8.44 billion, this figure has since declined to USD7.55 billion in 2022. Food exports on the other hand, have been on a continuous downward trend, ending 2022 at USD1.16 billion. Figure 2 shows the historical data of Caribbean food imports and exports.

The dependence on imports makes the Caribbean extremely vulnerable to disruptions in the global economy, adverse weather, natural disasters and supply chain disruptions. Perishable items in particular are highly susceptible to global disruptions and would arrive with a shorter shelf life or at a higher cost.

Food Inflation in the Caribbean – an argument for food security

Food is one of the more volatile components of the consumer price index (CPI), a representative basket of goods used to measure to overall change in consumer prices. The effect which food has on the CPI depends on the relative weight in the CPI basket, which varies from country to country. Some examples are the US which assigns food a weight in the CPI between 13% – 14%, whereas the European Union assigns food a weight between 19% – 20%, and in Trinidad and Tobago food makes up 17.3% of the CPI. In Barbados, food and non-alcoholic beverages account for around 22% of the RPI basket.

Inflation erodes the value of money and is a key factor affecting food security. The FAO notes that access to adequate income is paramount and closely related to food security, simply put, being able to afford nutritious food affects one’s access to it. Given the vulnerabilities of the Caribbean to global events and price fluctuations, the effect of inflation tends to be more drastic. Using Trinidad and Tobago as an example, latest data from the Central Statistical Office’s (CSO) CPI show a value of 148.6 for the food price index as of June 2024, this represented a 2.3% increase in food prices since June 2023, however, when compared to the onset of the pandemic (March 2020) the food price index value increased from 117.4 to its current level, an 26.6% rise in food prices.

This significant increase in food prices was not unique to Trinidad and Tobago; regional prices have risen sharply since the pandemic as a chain of events exacerbated an already dire situation in the Caribbean. Global shutdowns, travel restrictions, and the ensuing spike in shipping costs mounted pressure on Caribbean economies and further fuelled high food inflation, contributing to food insecurity.

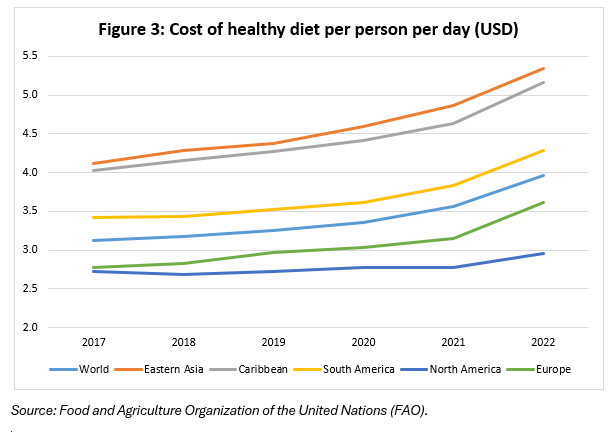

Further, from a regional perspective, the Caribbean has the second highest cost of a healthy diet according to the FAO’s report “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in The World 2024.” The FAO measures the cost at PPP dollars, a conversion that expresses the purchasing power of different currencies in common units. As of 2022, the Caribbean region had a per person per day cost of USD5.16, slightly behind the highest region, Eastern Asia, at a cost of USD5.34. Figure 3 shows the cost of a healthy diet in select regions.

The cost of a healthy diet in the Caribbean has increased by 20.8% since the end of 2019, with the largest increases being in Trinidad and Tobago (24.8%), and the Bahamas (24.1%), whereas the smallest increase was in the British Virgin Islands (5.8%).

CARICOM 25 by 2025 – a plan to tackle food insecurity

In a bid to ensure food security throughout the region, CARICOM member states have developed vision 25% by 2025. The plan was a proposal submitted by the CARICOM Private Sector Organisation (CPSO) and was approved in 2020. The ambitious vision aims to reduce the value of the regional food bill by 25% by 2025 through six focus areas aimed at promoting the productive capacity and efficiency of regional agriculture while also improving regional integration and trade policy. The six focus areas are listed below:

- Remove barriers to entry into Agriculture and encourage greater private sector participation.

- De-risk the Agricultural sector through providing financing and insurance options.

- Improve regional transport and logistics for agricultural products.

- Improve research and production in agriculture and adapt to climate change needs.

- Digitization of the regional agricultural sector.

- Revise the Common External Tariff (CET) regime in region and revisit “Rules of Origin”.

A ministerial task force comprising of agricultural ministers of member nations guides the implementation of policies aimed towards achieving the goals of the plan. The task force also meets monthly to share progress and provide guidance on the transformation of the agricultural sector.

Steps in the right direction – progress made thus far

Since its approval in 2020, CARICOM has been making solid progress in meeting the goal set out. In its February 2023 meeting, it was revealed that CARICOM met 57% of the targets set to improve the region’s food import bill, with production targets on cocoa, dairy, meat, root crops, fruits, and poultry reaching over 70% of their goal set for 2025.

There has also been the removal of non-tariff trade barriers through the implementation of key policy actions. The CARICOM trade policy for animals and animal products, approved in the 94th Council on Trade and Economic Development (COTED) Ministerial meeting. The policy enables a single regulatory environment for trade and import of animal and animal products, implementation of measures to facilitate trade throughout the region, and bring CARICOM in line with international best practices.

The Model Pesticides draft bill was also approved in August 2020. The bill’s primary objective is to serve as a basis for regional revision of pesticide legislations to minimize the risks they pose. The bill also mandates the establishment of a regulatory authority in member countries. Further, procedures to facilitate resolution of Sanitary and Photosanitary (SPS) disputes were established; the decision to adopt the procedures was made on the 104th COTED meeting. Under the policy, technical and impartial recommendations will be made according to the World Trade Organization SPS agreement.

Further positive developments throughout the region since include increased budgetary allocations for agriculture, increased infrastructural and cross border agricultural investment among CARICOM member states, launch of the USD5 million Caribbean Agricultural Productivity Improvement Activity (CAPA) project, implementation of a CNFO/CRFM Small-Scale Fisheries Action Plan aimed at increasing fish production through small-scale fisheries.

Challenges still persist

Despite the progress made and commitments by governments, the region still faces challenges in attaining the goal of food security. The most pressing challenge is the vulnerability to natural disasters, adverse weather, and climate change. In early July 2024, Hurricane Beryl made landfall in Barbados, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, and Jamaica as a Category 5. While the exact value of the damages is still being determined, there are preliminary analyses to show the extent; the UN office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates that in St Vincent and the Grenadines 75% of fruits in coastal and southern areas of the Grenadines has been destroyed while in Grenada there has been 80% loss in tree and staple crops. In Jamaica, preliminary estimates place damages to the agricultural sector at USD6.4 million. Finally for Barbados the fishing industry was hit the hardest, with 220 out of 312 active boats being lost.

The damage sustained from Hurricane Beryl have dealt a serious blow to the progress made since 2020, with the countries hit hardest originally on track to meet the goal of reducing food imports by 25% by 2025. A short-term plan is expected to be formulated by the ministerial task force, aimed at rebuilding the regional agricultural sector in light of the major setback faced by Hurricane Beryl.

Conclusion

Food security in the Caribbean has been a pressing issue since the COVID-19 pandemic’s drastic effect on the global economy highlighted pre-existing vulnerabilities. As a response, vision 25% by 2025 was developed as a potential mitigant, promoting regional production and cooperation to cut food imports and make the region more food secure. While progress has been made towards achieving this goal, Hurricane Beryl has wiped out much of the progress made, particularly in the Eastern Caribbean. Should the region be successful in reconstruction efforts following Beryl and achieve the goal of reducing food imports by 25% by 2025, food security should have noticeable improvements. That being said, there is still a long road ahead in undoing decades of agricultural neglect to achieve food security.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.