Sovereign Wealth Funds – Saving for a Rainy Day

Commentary

There are many examples around the world and throughout history to remind us of the ‘curse’ that comes with the discovery of natural resources and which many resource-rich nations face. The infamous ‘Dutch Disease’ can ‘infect’ countries if prudent policies are not in place to ensure that the windfall revenue is used efficiently and practically. Managing the depletion of a resource endowment is critical to ensure that future generations also benefit from the natural resource, which in many cases are non-renewable and exhaustible in nature. This is where the establishment of a rainy-day fund becomes necessary; not just for intergenerational wealth, but to assist with fiscal smoothing particularly during economic downturns. The economic cycles in countries that are heavily reliant on natural resources tend to be very volatile as they are highly dependent on the external environment. This usually results in procyclical fiscal policy such that economic booms are accompanied by expansionary fiscal policy and economic busts are accompanied by contractionary fiscal policies such as expenditure cuts and higher taxes.

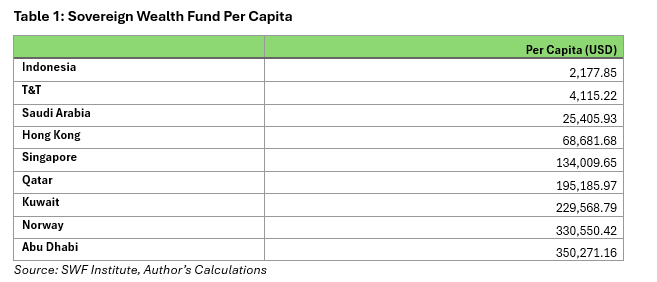

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) is a government-owned investment fund, set up for a variety of macroeconomic purposes, including the facilitation of saving and intergenerational transfer of proceeds from non-renewable resources and to help reduce boom and bust cycles driven by changes in commodity export prices. The first SWF – the Kuwait Investment Authority – was established in 1953 by the Kuwaiti Government to invest its oil revenue for future generations. Kuwait’s SWF is valued at just under USD1 trillion as of November 2024 and is the world’s fifth largest SWF. According to data from the Sovereign Wealth Institute, the total value of the top 100 SWFs globally stood at around USD13.7 trillion, with Norway, China and Abu Dhabi with the largest funds, based on the asset values.

T&T’s Heritage and Stabilization Fund

The Heritage and Stabilization Fund (HSF) is Trinidad and Tobago’s (T&T) SWF. According to the Heritage and Stabilization Fund Act, 2007, the purpose of the HSF is to save and invest surplus petroleum revenue derived from production business, to:

- Cushion the impact on or sustain public expenditure capacity during periods of revenue downturn whether caused by a fall in prices of crude oil or natural gas

- Generate an alternate stream of income so as to support public expenditure capacity as a result of revenue downturn caused by the depletion of non-renewable petroleum resources

- Provide a heritage for future generations of citizens of T&T from savings and investment income derived from excess petroleum revenues.

There are specific conditions under which withdrawals from the HSF is allowed – the Act specifies that withdrawals may be made based on the lesser amount of:

- Either 60% of the amount of the shortfall of petroleum revenues for that year, or

- 25% of the balance standing to the credit of the Fund at the beginning of that year.

Further, no withdrawal may be made in any financial year where the standing balance to the credit of the Fund would fall below USD1 billion if such withdrawals were to be made.

In terms of deposits, a minimum of 60% of the aggregate excess revenues shall be deposited to the Fund during a financial year.

In March 2020, the Act was amended to include further conditions of withdrawals, including when:

- A disaster area is declared under the Disaster Measures Act

- A dangerous infectious disease is declared under the Public Health Ordinance

- There is, or likely to be, a precipitous decline in budgeted revenues which are based on the production or price of crude oil or natural gas.

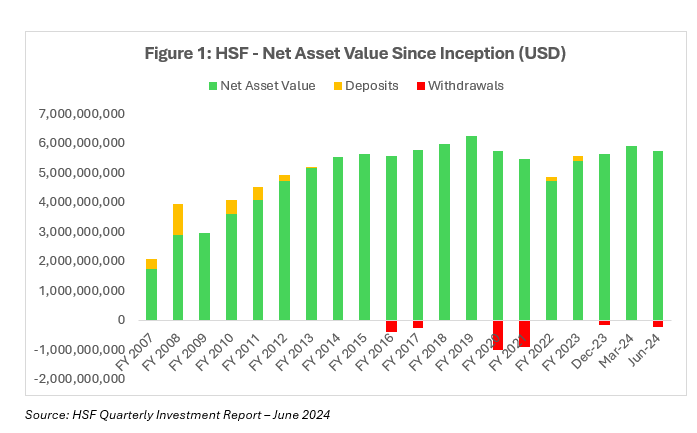

Since its inception, the accumulation of assets in the HSF has been admirable and has certainly provided much needed financial buffers for T&T, especially during economic slumps. It proved to be an important source of supplemental revenue during the COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in economic stagnation, dwindling government revenues and a sharp increase in expenditure.

During the height of the pandemic, in FY2020 and FY2021, a total of USD1.9 billion was withdrawn from the HSF. More recently, in December 2023, a further USD160.4 million was withdrawn to meet budgetary needs and during the June 2024 quarter, the HSF was again tapped into for an additional USD209.6 million, bringing the total withdrawals from the fund to around USD370 million or approximately TTD2.5 billion for FY2024.

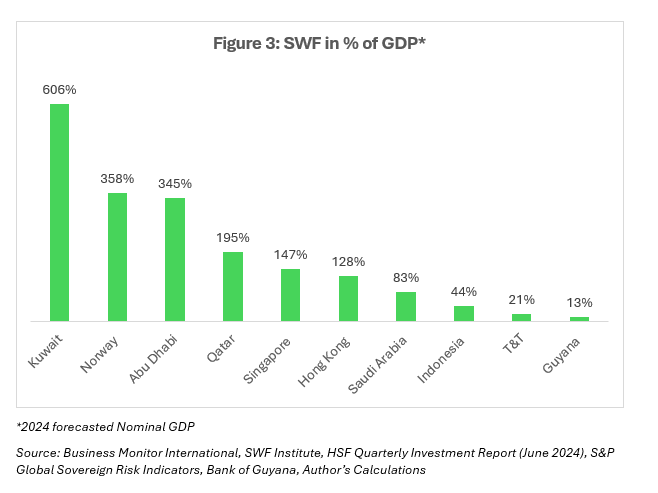

In the June 2024 quarterly investment report for the HSF, the net asset value (NAV) of the Fund stood at USD5.76 billion, 2.3% below that of the NAV at the end of the previous quarter. The assets were equivalent to around 21% of forecasted 2024 GDP– a notable accumulation of financial assets, but how does T&T compare to other commodity-dependent economies?

Figure 3 shows the size of major commodity-exporters’ SWFs relative to the size of their economies – Kuwait’s USD980 billion Fund represents around 600% of the country’s GDP, while Norway’s USD1.7 trillion fund is around 360% of its almost USD500 billion economy. Guyana, whose Natural Resource Fund was established by the Natural Resource Fund Act 2019, has since accumulated USD3.1 billion as at the end of October 2024 – 13% of the country’s forecasted GDP for 2024.

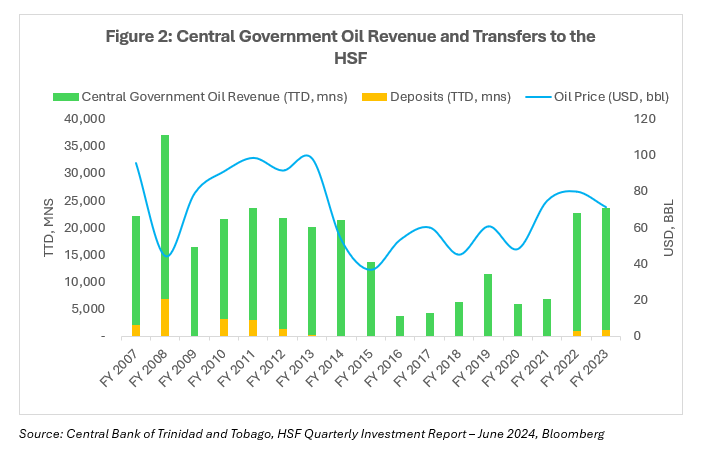

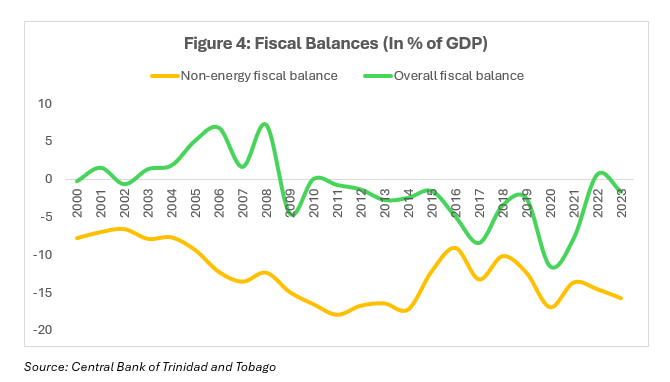

As with most commodity exporters, central government revenue closely aligns with the global price of oil and/ or gas. There were two major turning points in the global energy market, in 2008-2009 and then in 2014-2016. The former was largely due to the impact of the 2008 financial crisis, while the latter was due to a structural shift in the energy market driven by a supply glut from OPEC’s decision to abandon price controls as US shale production mushroomed. Coupled with the lower international energy prices, T&T’s energy revenue was also negatively impacted by declining domestic production. These dynamics have resulted in a significant decline in central government oil revenue, which since 2016 has not fully recovered. It was not until 2022-2023 when prices rallied significantly on rising geopolitical risks and the post-COVID surge in demand that government oil revenues were able to recover.

Since 2007, the T&T central government has earned approximately TTD273 billion from oil revenue, with the largest single FY intake of TTD30 billion in 2008 and the second largest of TTD22 billion in FY2023. During the same period, there have been eight years where contributions were made to the HSF, totaling just under TTD1.9 billion. This represents around 7.2% saved from the total oil revenue earned since FY 2007, which is when the HSF was formalized.

The HSF has helped to smooth fiscal policy and can partially mitigate the need for sharp fiscal adjustments which can negatively impact the economy. It is imperative that the country continues to accumulate financial buffers, given its exposure to commodity price shocks. For commodity exporters like T&T, an important indicator of vulnerability is the non-energy fiscal balance, which is the difference between non-energy revenue and total expenditure – it essentially measures whether non-energy sector revenue can sustain all of government expenditure.

Historically, T&T has run successive and very high non-energy fiscal deficits since 2000, averaging around 12.5% of GDP, compared to an average deficit of 1.1% of GDP in the overall fiscal account. At the end of FY 2023, the non-energy fiscal deficit stood at TTD31 billion up from TTD28 billion at the end of FY 2022. Further, according to data from the CBTT, the non-energy primary balance, which measures the government’s ability to pay for public goods and services using only its non-resource generated revenue, posted a deficit of around TTD25 billion at the end of FY 2023. This highlights a major underlying risk to fiscal sustainability as it underscores the country’s dependence on energy revenues.

The importance of financial buffers to the T&T economy is evident, especially given the country’s past experiences with severe commodity price shocks. During the 1980’s oil price crash, the government of the day would have expended its energy windfall from the boom of the previous years to establish the petrochemical industry, which has been able to propel the economy in the subsequent decades. During 1982 – 1993, GDP had declined by a cumulative 25%, the stock of international reserves was eroded at an alarming rate plummeting from USD3 billion to USD200 million, while external debt rose from 13% of GDP to almost 50% and public finances had deteriorated significantly. These factors culminated in a dire economic situation of debt distress and IMF intervention for the T&T economy.

If nothing, the painful past should serve as a valuable lesson on the importance of financial cushions, especially now – given the outlook for the global economy, the widely erratic geopolitical environment and the thrust towards cleaner and greener energy in the near future, which will all have implications for the global energy markets. The need for fiscal prudence in T&T is even more important in this context and will entail some degree of fiscal adjustment to align the non-energy revenue with government spending thereby reducing the non-energy fiscal deficit to more sustainable levels. Insulating the economy from negative terms of trade shocks caused by fluctuating commodity prices can be achieved through a robust SWF. A recent paper by the IMF concluded that a stabilization SWF helps smooth fluctuations in budget resources by reducing or eliminating the uncertainty and volatility of resource-related revenue flowing into the budget. Further the empirical results show that fiscal policy volatility in countries with stabilization SWFs is lower, relative to that in countries without such a fund, by about 14%. The establishment of a SWF is critical, but it is not a substitute for fiscal policy and must work in tandem to ensure fiscal sustainability and proper management of a non-renewable resource.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.

[1] Using an average exchange rate of TTD6.53/ USD1 – which is the average buying and selling rate during 2007 – 2023.

[2] Ali J. Al-Sadiq and Diego Alejandro Gutiérrez (2023), “Do Sovereign Wealth Funds Reduce Fiscal Policy Pro-cyclicality? New Evidence Using a Non-Parametric Approach”, IMF Working Paper WP/23/133, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund