Tourism In the Caribbean

Commentary

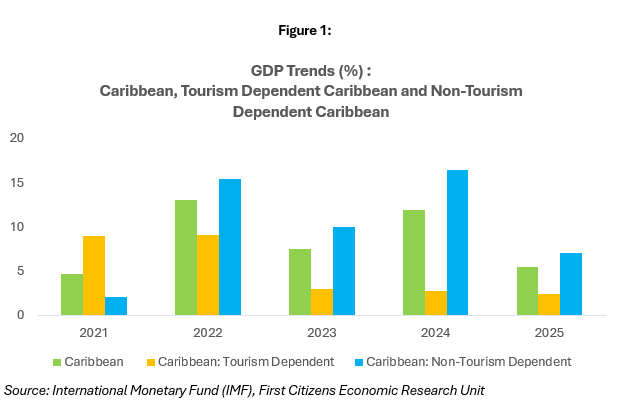

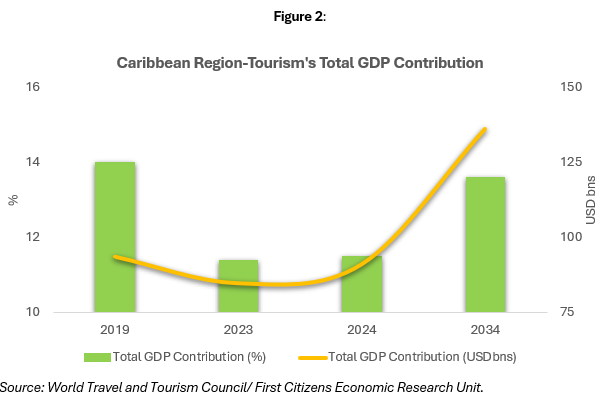

The tourism sector directly accounted for approximately 11.4% of the Caribbean’s GDP (Figure 2) in 2023, amounting to approximately USD84.9bn. This figure is projected to rise marginally to 11.5% (USD91.2bn) in 2024, with long-term forecasts predicting a more significant increase to 13.6% by 2034, equivalent to USD136.1bn, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). While these numbers paint a picture of growth, they also reveal the risks of over-dependence on a singular industry. The Caribbean’s economic fortunes are increasingly tied to the fluctuations of global tourism trends, leaving it exposed to external shocks, from pandemics to climate change and shifting travel preferences.

Jamaica: A Resilient but Vulnerable Tourism Economy….

Jamaica stands as a quintessential example where tourism is the cornerstone of its economic activity. According to the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ), tourism is one of the country’s fastest-growing sectors, contributing over 30% of GDP and one-third of all jobs, both directly and indirectly. Over the past three decades, the sector has expanded by an impressive 36%, cementing its position as the largest generator of foreign exchange. The WTTC, reports that tourism’s contribution to Jamaica’s GDP reached 33.6% in 2023, with projections indicating a slight dip to 33.3% in 2024, before climbing to 40.4% by 2034.

Jamaica’s post-pandemic tourism recovery has been nothing short of remarkable. In 2023, the country welcomed a record 4.2mn visitors (Figure 3), and generated USD4.38bn in revenue, according to the Minister of Tourism. Data from Tourism Analytics highlights a 17.7% increase in stopover arrivals in 2023, driven by strong demand from key markets such as the US, Canada, and the UK. This momentum continued into early 2024, with 1.34mn arrivals recorded in the first quarter alone. By the end of 2024, Jamaica was expected to have hosted approximately 4.3mn visitors, with earnings reaching USD4.3bn. These numbers reflect the sector’s resilience and its critical role in the country’s economic rebound.

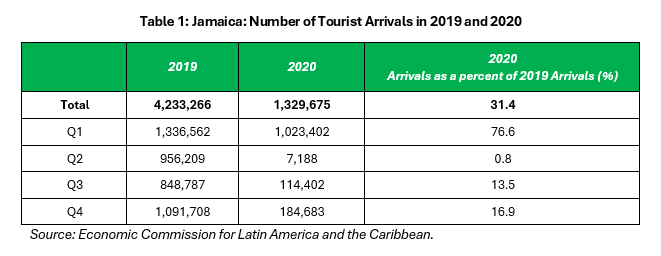

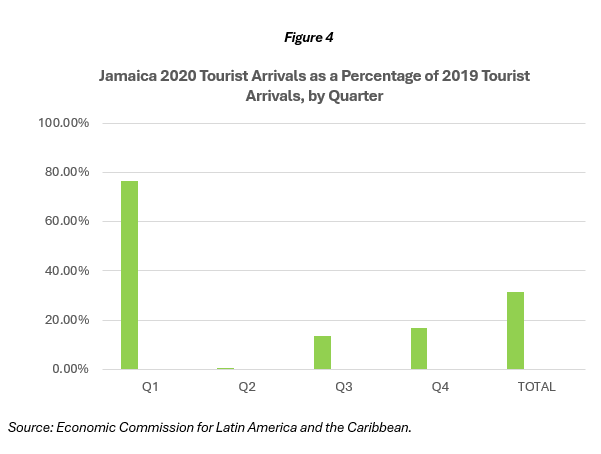

However, Jamaica’s heavy reliance on tourism remains a structural vulnerability. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) ranked Jamaica as sixth most dependent in the Latin America and the Caribbean region on its 2019 tourism dependency index, with a score of 38.7. The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the risks of this dependency. In 2020, real GDP contracted by 10%, according to the IMF, as international tourism ground to a halt. Government data revealed that arrivals plummeted to just 31% of pre-pandemic levels, with second-quarter figures declining to less than 1% of the previous year’s totals. The resulting spike in unemployment, widening fiscal deficits, and overall economic uncertainty emphasized the fragility of a tourism-driven economy.

While Jamaica’s tourism recovery has been strong, long-term economic stability remains uncertain. The government aims to attract 5mn visitors and generate USD5bn in earnings by 2025, building on the sector’s post-pandemic momentum. However, external factors—such as global economic conditions, inflationary pressures in key markets, and geopolitical disruptions—pose significant risks. Jamaica’s reliance on North American travellers, who constitute the majority of arrivals, further exacerbates its sensitivity to economic fluctuations in the US and Canada.

The Bahamas: The Engine of Growth and Vulnerability

Tourism is the lifeblood of The Bahamian economy, driving growth, employment, and foreign exchange earnings. However, this reliance also exposes the country to significant risks. The COVID-19 pandemic and Hurricane Dorian in 2019 starkly illustrated these vulnerabilities. Hurricane Dorian, the most expensive disaster in the nation’s history, caused unprecedented devastation in Abaco and Grand Bahama. Recovery efforts were still underway when the pandemic struck, compounding the economic strain. According to the IDB, the pandemic’s economic toll between 2020 and 2023 reached BSD9.5bn – 2.7 times the cost of Hurricane Dorian’s damages. Combined, these crises inflicted BSD13.1bn in economic losses, leaving The Bahamas in a precarious position ahead of future hurricane seasons.

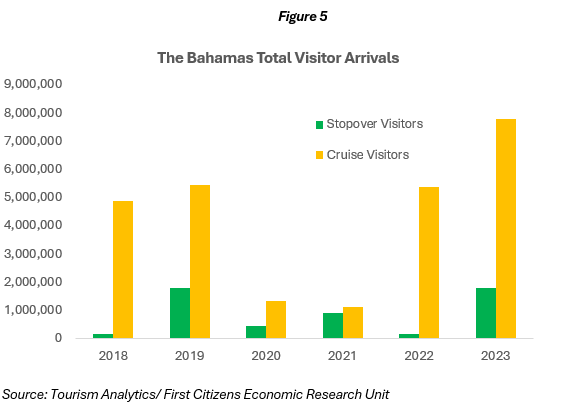

Despite these setbacks, tourism has been the linchpin of The Bahamas’ economic recovery. Data from Tourism Analytics shows a significant rebound in visitor arrivals, from 2mn in 2021 (Figure 5) to 6.8mn in 2022 and a record 9.6mn in 2023. The first half of 2024 saw a 14% year-on-year increase, with 5.7mn arrivals, positioning the country to surpass 2023’s figures. The Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Tourism projects at least 10mn tourist arrivals in 2025, emphasizing expectations of sustained sectoral growth.

Even as activity in the tourism sector remains resilient, climate change poses an existential threat to its outlook. Rising sea levels, increasing hurricane intensity, and biodiversity loss are eroding The Bahamas’ most valuable tourism assets: its coastal infrastructure, luxury resorts, and pristine beaches. These natural assets are not only the foundation of the tourism industry but also the backbone of the broader economy. The IMF highlights that climate-related risks, such as intensifying hurricanes and rising sea levels, could severely undermine the country’s natural capital, further exacerbating economic fragility.

Despite the strong post-pandemic recovery, structural constraints persist. The IMF warns that capacity limitations, particularly in hotel accommodations, could hinder further tourism expansion. While new hotel projects and the rise of short-term rentals may alleviate some of these pressures, their success depends on investment flows and effective policy execution.

Trinidad and Tobago: A Unique Economic Model….

Unlike its tourism-dependent Caribbean neighbours, Trinidad and Tobago’s (T&T) main economic sector is energy. According to the IMF the energy sector accounted for approximately 36% of T&T’s nominal GDP in 2022 and upwards of 80% of total export earnings, emphasizing the nation’s reliance on hydrocarbons and highlighting its vulnerable to external shocks, such as fluctuations in global oil and gas prices, which can have ripple effects across the economy.

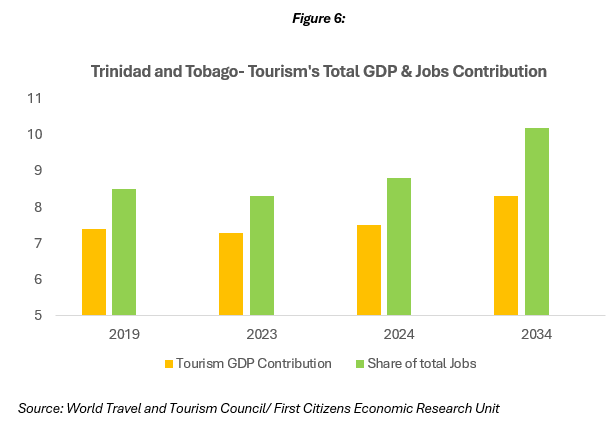

Although tourism is not a primary economic pillar for T&T, it still plays a vital role in employment generation and foreign exchange earnings. According to the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), in 2023, the tourism sector contributed 7.3% to total GDP, with projections indicating an increase to 7.5% in 2024 and 8.3% by 2034. (Figure 6)

Employment within the tourism industry follows a similar trajectory. In 2019, tourism-related jobs accounted for 8.5% of total employment, which slightly declined to 8.3% in 2023 but is expected to rise to 8.8% in 2024 and further to 10.2% by 2034. These figures indicate that, despite its secondary status in the national economy, tourism remains an essential driver of employment, particularly for service-oriented sectors such as hospitality, transport, and retail.

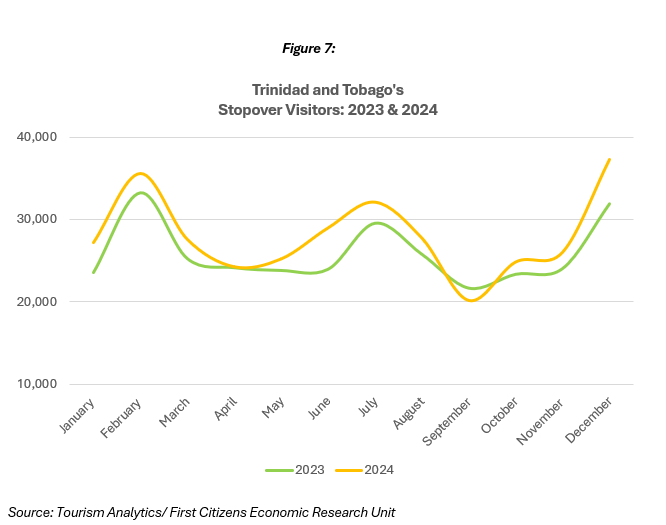

From a regional perspective, T&T’s tourism dependency remains lower than Jamaica or The Bahamas, both of which have significantly higher tourism GDP shares. However, within T&T itself, Tobago’s economy is more reliant on tourism, with a mix of domestic and international visitors. While domestic travellers from Trinidad constitute a significant share of arrivals, international visitors—primarily from Europe and North America—remain key contributors to Tobago’s hotel and resort sector. According to Tourism Analytics, T&T’s stopover visitor arrivals in 2023 experienced an 8.5% increase in 2024, rising from 310,237 visitors in 2023 to 336,696 in 2024. This steady increase indicates a gradual recovery and expansion of the tourism sector post-pandemic. (Figure 7)

Carnival: A High-Value Tourism Driver

One of the most lucrative tourism attractions in T&T is its world-renowned Carnival, often described as the “Greatest Show on Earth.” Unlike traditional sun-and-sand tourism models seen in the rest of the Caribbean, T&T’s Carnival provides a high-value, event-driven tourism product, generating substantial economic activity.

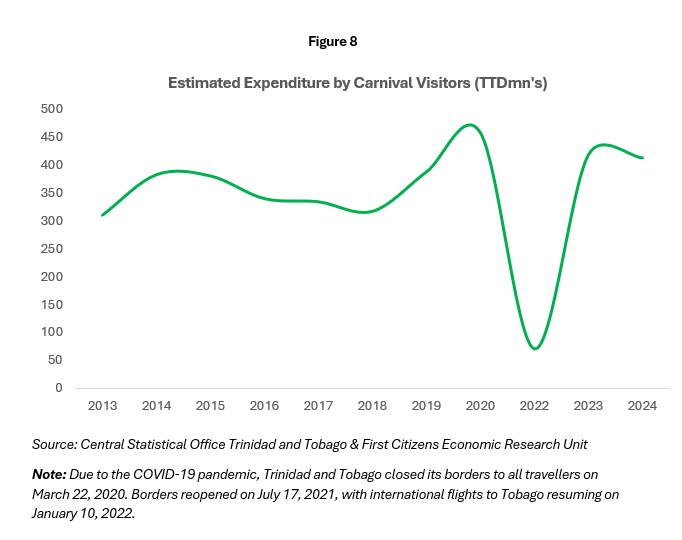

The event contributes approximately TTD400mn (Figure 8) annually, with spending spread across various sectors, including hospitality, retail, transportation, and entertainment. As a seasonal economic stimulant, Carnival drives short-term booms in employment, foreign exchange inflows, and business revenues, benefiting both formal and informal sectors. Projections suggest even greater financial gains in the coming years. Tourism Minister Randall Mitchell forecasts that foreign visitor spending during Carnival 2025 could surpass TTD640mn, reflecting the festival’s increasing global appeal and its potential as a growth lever for the tourism sector.

The Tourism Diversification Challenge:

Tourism remains a dominant economic driver across the Caribbean, contributing significantly to GDP, employment, and foreign exchange earnings. However, excessive dependence on this sector exposes regional economies to substantial risks, particularly amid climate-related disruptions, global economic fluctuations, and evolving consumer preferences. The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized these vulnerabilities, triggering an unprecedented collapse in visitor arrivals and revenue. Without strategic diversification, Caribbean nations face heightened economic instability and reduced capacity to withstand future shocks.

Structural Challenges in Caribbean Tourism:

- Market Concentration Risks – The region’s reliance on North American and European travellers introduces systemic exposure to external downturns. A US or EU recession could lead to declining disposable incomes, directly impacting visitor flows to destinations like the Dominican Republic and the Bahamas.

- Climate Change Threats – Rising sea levels, coral bleaching, and intensifying hurricanes endanger key tourism infrastructure. For instance, Barbuda faced near-total devastation from Hurricane Irma, while Jamaica’s coastal resorts experience increasing erosion.

- Lack of Economic Diversification – Tourism’s outsized role in GDP leaves little room for economic shock absorption. In islands such as Saint Lucia and Antigua & Barbuda, where tourism exceeds 60% of GDP, contractions in visitor spending have widespread ripple effects.

- Inflationary Pressures in Source Markets – Rising airfare, accommodation costs, and currency fluctuations (e.g., USD appreciation) erode price competitiveness, making destinations like Barbados less attractive compared to budget-friendly alternatives in Southeast Asia.

Recommendations:

Caribbean nations should pursue strategic diversification to bolster economic resilience. Expanding into sectors like renewable energy, agribusiness, and digital services – such as Jamaica’s expanding Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry, can provide alternative revenue streams. Within tourism, diversifying offerings to include eco-tourism, heritage tourism, medical tourism and sport tourism can attract new markets, reducing dependence on North American visitors. Investing in climate adaptation, strengthening infrastructure resilience, and improving regional air and sea connectivity will help mitigate environmental and economic vulnerabilities. Additionally, implementing policy reforms focused on workforce development, fostering public-private partnerships, and enhancing regional cooperation are essential for long-term stability. By balancing tourism expansion with diversification, Caribbean nations can safeguard economic growth against future shocks.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, while tourism remains a cornerstone of the Caribbean economy, the region’s heavy reliance on this sector exposes it to significant vulnerabilities. To enhance economic resilience and sustainability, Caribbean nations must prioritize diversification strategies that encompass economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, promoting sustainable tourism practices, and fostering economic diversification are essential steps toward building a more robust and adaptable economy. By implementing these measures, the Caribbean can better navigate future challenges and ensure long-term prosperity for its communities.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.