Money Laundering In the Caribbean

Insights

The world of Financial Crimes covers a variety of offences carried out by individuals or groups with one common goal of obtaining some economic benefit through illegal means. Some of the most common financial crimes committed are money laundering, terrorist financing, fraud and tax evasion. In order to combat the different financial crimes, countries around the world have established agencies dedicated to identifying and preventing these crimes. While difficult to exactly quantify, estimates from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) show that the cost associated with money laundering ranges from USD800 billion – USD2 trillion per year globally or around 2% – 5% of global GDP.

What is money laundering?

Money laundering is the illegal process of making large amounts of money generated by criminal activity, such as drug/sex/human trafficking or terrorist financing, appear to have come from a legitimate source. The money from the criminal activity is referred to as ‘dirty’, and the process of money laundering, as summarized below, “washes” it to make it appear legitimate. There are three stages of money laundering.

- Placement – Placing the “dirty money” into a legitimate system such as a bank or another business. The large sums are often broken up and may be moved into financial instruments or bank accounts.

- Layering – This is where multiple ‘layers’ are added to conceal the transaction. The more layers there are, the more concealed the transaction, by simulating multiple transactions with no commercial benefit, except to conceal the true nature of the illicit or illegal activity. Here, multiple deposits are utilized by the launderer, each usually below the cash disclosure/reporting requirement. Many different accounts might also be used to provide an added layer of concealment.

- Integration – In this final stage, the money launderer has managed to conceal the illegal source of the money to be deposited so that the funding appears legitimate. This is typically done by maneuvering several transactions, typically ending with the purchase of luxury assets or placement in financial instruments or certain investments.

An example of the money laundering cycle is illustrated below:

Popular channels through which money is laundered are:

- Real Estate: Transactions in the real estate sector are by nature, large and involve multiple parties (the parties layering the transaction), making it an attractive sector for money launderers. According to research conducted by Henry et al in 2020, the real estate sector is used to “convert dirty money into a secure and long-term investment[1]”. An indicator of money laundering in a country may be the presence of a real estate industry in which demand has little fluctuation regardless of fluctuations in prices.

- The gaming industry: Similar to that of the real estate industry, the gaming industry involves large cash transactions. Regulation of the industry is fairly limited in multiple developing jurisdictions such as the Caribbean and Latin America, making it an attractive option for money launderers.

- Automobile market: Vehicles, especially luxury or high-priced vehicles are sometimes purchased to legitimize money that is laundered.

- The informal economy: In the informal economy, cash transactions are typically used and much of the income earned from this industry is not disclosed, meaning that the size can often be understated. In countries with large informal economies and little enforcement of Anti-Money Laundering legislative requirements, transactions tend to be highly volatile. Consumption of luxury goods is occasionally high, and capital flows fluctuate significantly.

- Shell Companies: One of the avenues used for ‘investments’ by money launderers is through the establishment of shell companies. They are easy to form and operate anonymously, often with no obvious commercial or basis for their formation or operation.

How has crypto currency affected laundering?

Crypto currencies are relatively new in the financial system, gaining prominence in recent years due to their sharp increase in price (though, prices have dropped significantly as many nations have clamped down on the currency). Many advocates for crypto currencies claim that money laundering with crypto is highly complex and risky, with a greater level of transparency and accountability than physical money due to the blockchain and peer to peer networks used, however, the blockchain does have some level of anonymity in transactions carried out in the network, allowing criminals to still find ways to exploit the currency for money laundering purposes.

A large portion of reported cryptocurrency money laundering activity consisted of funds simply being sent directly through exchanges to the end address, however, Chainalanysis, a blockchain data platform, highlighted two more sophisticated methods:

- Use of crypto mixers – platforms which hide the origin and destination of cryptocurrency.

- Chain hopping – moving funds from one blockchain to another by using “bridges”.

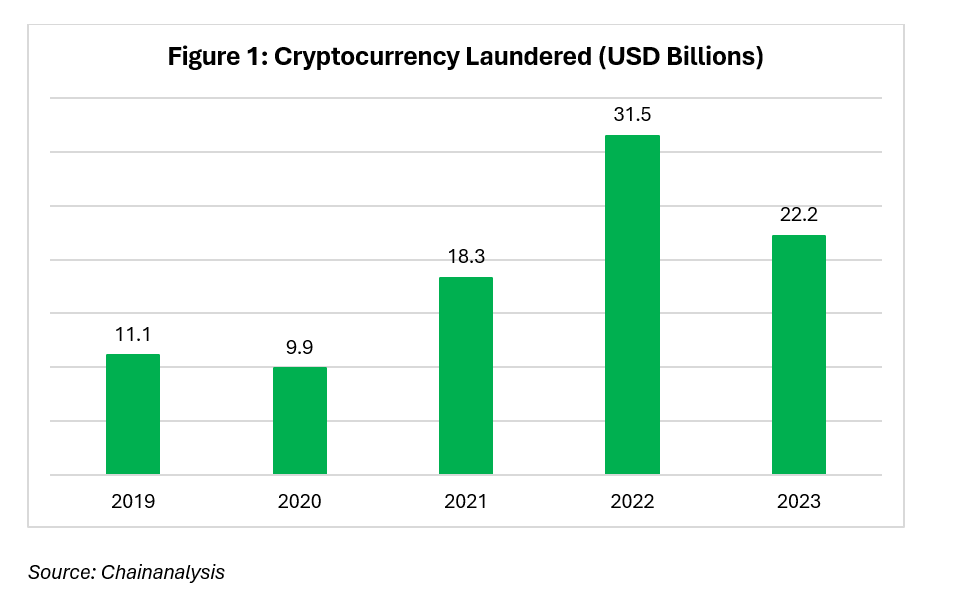

Estimates by Chainanalysis, indicate that the amount of laundering that occurred with cryptocurrency increased peaked in 2022 at USD31.5 billion, a significant increase from pre-pandemic trends. Figure 1 shows the estimated amount of money laundering that occurred through cryptocurrencies.

The effects of Money Laundering on the economy

Money laundering has significant implications on an economy, including weakened GDP growth, imbalances in foreign payments, heightened inflation and higher levels of unemployment because no real income is generated and there is no real increase in actual business or commercial activity. One of the main reasons for laundering money is tax evasion, which has negative implications for an economy. Taxes are the largest stream of government revenue and tax evasion can have significant implications for government revenue collection, which for small economies with already limited revenue base, further erodes fiscal flexibility. Further, money laundering can negatively impact legitimate private sector businesses. Shell companies are a tool used to launder money. Since the main goal is to legitimize illegal funds, many shell companies do this by offering goods and services at below market rates, which reduces the competitiveness of legitimate businesses.

Moreover, if a money launderer successfully passes money through the financial system, financial institutions can be affected by sudden and large shifts in assets and liabilities, directly affecting the institution’s stability. Further, heightened scrutiny from regulators, auditors, and the public can result in considerable reputational damage. These two factors can cause significant volatility in the financial system.

At the integration stage of the money laundering process, the launderer is most concerned with inflows and outflows of cash to make the funds appear legitimate. This in turn would see a significant increase in demand for luxury goods[2] which can affect the level of imports, exports, and foreign currency reserves of a country, causing volatility in a country’s external liquidity. Furthermore, a country’s competitiveness and business environment can be adversely affected if it is found to be highly vulnerable to money laundering. One of the direct effects of reputational loss would be a decrease in investments, both domestic and international. On the international side, financial institutions do not conduct transactions with countries that have been ‘sanctioned’ or involved in either terrorist or proliferation financing. Enhanced due diligence procedures would be applied with transactional limits to those countries deemed as high risk with little or no money laundering legislative requirements and/or enforcement mechanisms.

Anti-Money Laundering

In the global fight against money laundering, Anti-Money Laundering (AML) policy framework was developed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The FATF was established in 1989 following a G7 conference in Paris. The FATF is regarded as “the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.” It is an inter-governmental body that formulates the regulations necessary to fight money laundering and uses its influence over countries to operationalise these AML recommendations into laws and regulations in the said countries and create mechanisms to monitor and enforce compliance by financial and other entities in the said countries in which they operate.

These AML laws, regulations and procedures are intended to prevent criminals from legitimising funds gained from illicit and other illegal activities. AML regulations require banks and other financial institutions that issue credit or accept customer deposits to follow rules that ensure they are not facilitating money-laundering. In addition to the overarching laws and regulations, specific AML guidelines are usually issued by a country’s central monetary authority, with heavy penalties being imposed on financial institutions and related entities that do not comply.

The Caribbean context

It is noted that countries across the Caribbean region have been classified as “jurisdictions with strategic deficiencies” by the FATF. Given the region’s proximity to Latin America, some academic researchers note that the position of the Caribbean makes it a “virtual maritime and aerial crossroads” between the US and Latin America, a factor which has exposed it to currency smuggling[3]. Citizenship By Investment (CBI) programmes have also been noted to pose a risk to the region with regards to money laundering. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) notes that insufficient background checks on individuals and the source of the funds being invested may see CBI programmes being misused, with risks being elevated if investors have some form of political affiliation.

The AML policy framework in the Caribbean is also guided by the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF). Anti-Money laundering regulations began in the Caribbean in 1990 as countries met to consider 40 AML recommendations laid out by the FATF, often referred to as the FATF 40. The “Kingston Declaration” in 1992 saw the region affirm its position in the fight against money laundering and led to the establishment of the CFATF. It was not until November 1996 that member states of the CFATF entered a Memorandum of Understanding to have the CFATF be a guide in implementing the policies outlined in the 1988 UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.

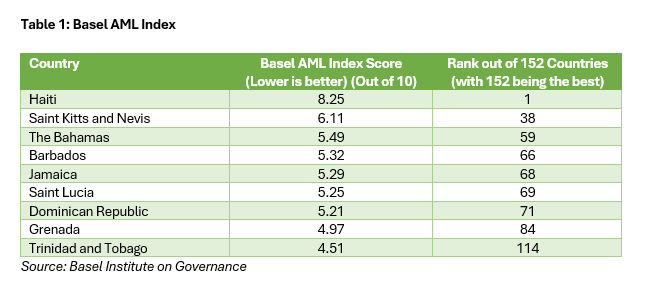

The Basel AML index assesses the risk of a country to money laundering. The index follows the methodology for assessing risk laid out by the FATF, and ranks countries based on a scale ranging from 1 – 10, where 10 is the highest risk. The associated risk score and ranking for Caribbean countries with sufficient data as of 2023 is as follows:

Notable removals from the FATF grey list

The FATF classifies countries with weak AML measures as either black or grey listed countries. Blacklisted countries are those with “serious strategic deficiencies to counter money laundering, terrorist financing, and financing of proliferation.” Grey listed countries are classified as “jurisdictions with strategic deficiencies,” however, they are actively working with the FATF to address these deficiencies.

As of October 2024, only one CFATF member country is listed in the FATF grey list, that being Haiti. Over the years several countries in the region have been removed from this grey list as continued steps are taken to combat money laundering. Some notable removals in recent years are Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, and Barbados.

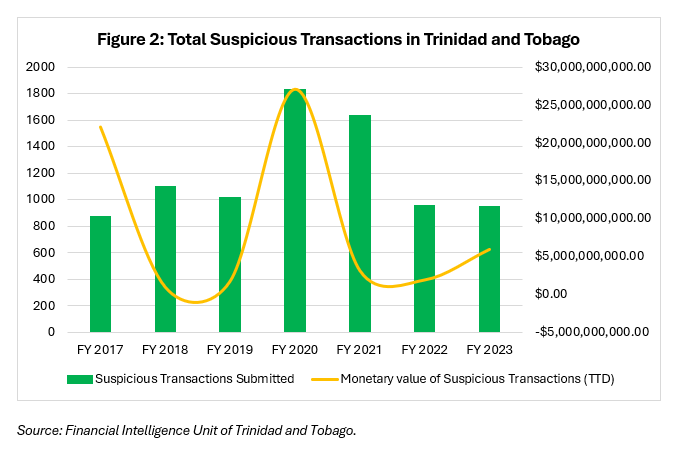

Trinidad and Tobago was removed from the FATF grey list in February 2020. Upon removal, the FATF noted that Trinidad and Tobago had made significant progress in improving AML effectiveness and had addressed deficiencies that were identified.

Figure 2 shows the total number of suspicious transactions flagged by the regulating authorities (Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and Tobago Securities Exchange Commission, and the Financial Intelligence Unit of Trinidad and Tobago).

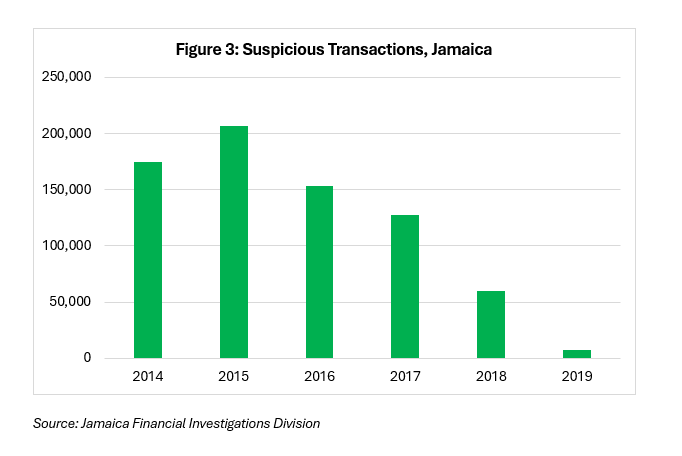

Jamaica was removed from the FATF’s grey list in June 2024 after being included on the list in 2020 following “significant progress in improving its AML/CFT regime”. Improvements in the AML/ combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) regime include a more comprehensive framework, inclusion of all financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions in the updated regime and improvement in the overall investigation process through more use of financial intelligence. Data on the number of suspicious transactions at the time of writing is significantly lagged, with the last update from the Financial Investigations Division being 2019.

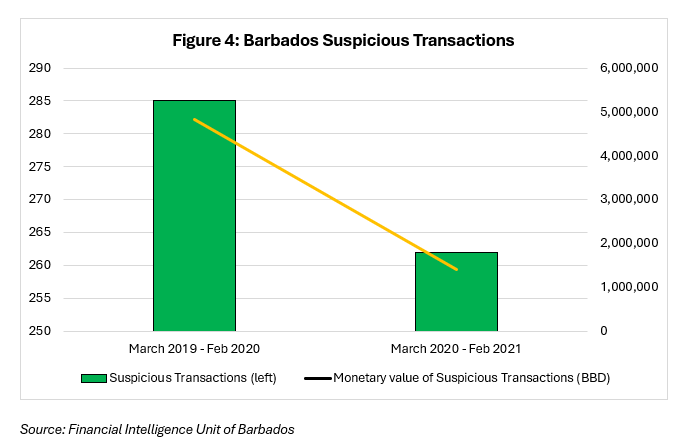

Barbados was removed from the FATF’s grey list in February 2024, making significant improvements in their framework. Improvements highlighted by the FATF were similar to that of Jamaica. Barbados continues its commitment towards the fight against money laundering, taking steps to improve legislation, enforcement, seizure of illicit funds, and improving its money laundering database.

Though available data is limited, the number of suspicious transactions as well as the associated monetary value in Barbados is shown in Figure 4.

Throughout the region, countries are working diligently with the CFATF to strengthen their AML regimes, to better identify and prevent the occurrence of money laundering and other financial crimes. There is considerable work still to be done to implement and to be in compliance with the 40 AML recommendations outlined by the FATF.

In the Eastern Caribbean, countries have been strengthening due diligence processes regarding CBI programmes. Governments of Grenada, Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis, Dominica, and St Lucia have or are currently working on restructuring their CBI programmes.

Conclusion

The fight against money laundering is one that is ongoing and ever changing, with criminals becoming more creative in their methods. Simultaneously, countries continue to adapt to avoid the negative social and economic consequences. Guidelines by the FATF will continue to aid countries in implementing effective policy measures to better identify and prevent instances of money laundering. In the Caribbean, while much progress has been made towards combating money laundering and other financial crimes since the formation of the CFATF, there remains much work to be done. Throughout the region, efforts are continuing to be complaint with all the recommendations laid out by the CFATF.

DISCLAIMER

First Citizens Bank Limited (hereinafter “the Bank”) has prepared this report which is provided for informational purposes only and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. The content of the report is subject to change without any prior notice. All opinions and estimates in the report constitute the author’s own judgment as at the date of the report. All information contained in the report that has been obtained or arrived at from sources which the Bank believes to be reliable in good faith but the Bank disclaims any warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, completeness of the information given or the assessments made in the report and opinions expressed in the report may change without notice. The Bank disclaims any and all warranties, express or implied, including without limitation warranties of satisfactory quality and fitness for a particular purpose with respect to the information contained in the report. This report does not constitute nor is it intended as a solicitation, an offer, a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell any securities, products, service, investment or a recommendation to participate in any particular trading scheme discussed herein. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable to all investors, therefore Investors wishing to purchase any of the securities mentioned should consult an investment adviser. The information in this report is not intended, in part or in whole, as financial advice. The information in this report shall not be used as part of any prospectus, offering memorandum or other disclosure ascribable to any issuer of securities. The use of the information in this report for the purpose of or with the effect of incorporating any such information into any disclosure intended for any investor or potential investor is not authorized.

DISCLOSURE

We, First Citizens Bank Limited hereby state that (1) the views expressed in this Research report reflect our personal view about any or all of the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report, (2) we are a beneficial owner of securities of the issuer (3) no part of our compensation was, is or will be directly or indirectly related to the specific recommendations or views expressed in this Research report (4) we have acted as underwriter in the distribution of securities referred to in this Research report in the three years immediately preceding and (5) we do have a direct or indirect financial or other interest in the subject securities or issuers referred to in this Research report.

[1] “The Impact Of Money Laundering In Beautiful Places: The Case Of Trinidad And Tobago” – Lester Henry and Shanice Moses (March 2020)

[2] “Money Laundering: Concept, Significance and its Impact.” Vandana Ajay Kumar (January 2012)

[3] “”A Tale of Two Regions: The Latin American and Caribbean Money-Laundering Connection.” Shazeeda Ali (February 1999)